The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act was introduced recently by representatives Anna Eshoo, Jan Schakowsky, and senator Cory Booker, and it immediately generated a lot of buzz within the marketing industry. But what is the bill really about, what areas are most important for businesses and advertisers to be aware of, and how worried should the industry be?

This article gives a full overview of the Banning Surveillance Targeting Act of 2022, covering the most important bits of legislation, key points, and the surrounding discussion.

Table of Contents

What Do They Define as “Targeted Advertising” or “Surveillance Advertising?”

The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act outlines a few different use cases for targeting data that have different levels of restriction. Here’s the best way to understand the different rule sets:

Third-Party Data

Any data purchased from a third party by either the advertiser or the platform/provider falls under the following protocol. Additionally, any first-party data the provider has that the advertiser does not is also considered third-party data.

For this circumstance, the bill differentiates targeting ads based on individually identifiable information and inherent traits versus targeting based on contextual information.

“Targeted advertising,” or “surveillance advertising,” as defined by the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act, is any material that can single out a specific person or device based on identifiable information about them such as their name, address, phone number, or email address. In addition, information that can figure out a person is a member of a protected group or class (e.g. a specific race or religion) would also be prohibited. More specifically, the bill in its current form defines “targeted advertising” as an ad provider or platform providing an advertiser or third party any of the following:

- A list of individuals or connected devices

- Contact information of an individual

- A unique identifier for any specific individual or device

- Any personal information that could be used to identify an individual or device

That last one might look like a repeat of the point before it, but it’s not – this is to specify that the bill also prohibits the use of information that could indirectly be used to figure out someone’s identity. For example, specific location data might not give an exact address of where you live or work or define which location is which, but someone can easily figure this out using it.

The bill specifies that a platform or provider cannot provide an advertiser or third party with this data, and they may not target, optimize, or analyze advertising on the basis of it.

The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act defines some examples of contextual information that it does not prohibit for ad targeting:

- Search history and terms

- Content that individuals engaged with or viewed

- Regionalized places

Zero and First-Party Data Directly From The Advertiser

Individually identifiable information from the advertiser themselves can be used, so long as it was not obtained from any other party or source. For example, if users consented to give their email address to a business in order to sign up for their newsletter, that email list is not prohibited by the Act to use for that specific business’ ads.

However, the first or zero-party data from the advertiser cannot identify an individual as a member of a protected class or contain information that would be able to identify them as such. Under Federal Law, a “protected class” is any race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, or disability.

The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022 would require a written confirmation from the advertiser that any lists they use have met these standards before being used – i.e. the data was not purchased or collected from any other party, nor does it define users as members of a protected class.

To What Extent Would Targeted Advertising Be Banned?

Anything that falls under the above bullet points would be prohibited entirely under the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022 (in its current form, that is — more on that later). So as it stands, a business seeking to advertise could only use their first-party data, with the exception of information like religion or gender, as well as contextual data from the platform or provider such as search history or previously viewed content. However, the platform/provider cannot give its own personally identifiable first-party data to the advertiser, nor can it use its personally identifiable first-party data to optimize or analyze ads even if the data is not given to or used by the advertiser directly.

The Federal Trade Commission would be in charge of enforcing the act, with penalties ranging from $100 – $1000 per violation. The FTC also has the right to add further specifications to the act if necessary.

The bill can be challenged in court under certain circumstances, with the Attorney General having the right to investigate and potentially give appeals for related court cases. However, this does not mean they can make exceptions on a case-by-case basis.

How Bad is the Act for Advertisers and Digital Platforms?

Simply put, it’s not as bad as it sounds for several reasons. However, it also depends on who you are. Here, we’re going to consider the hypothetical situation that the bill passes in its current state with no major changes. Later, we’ll briefly discuss why that’s unlikely.

Potentially Bad News For First-Party Data Platforms

Some platforms like Amazon and TikTok created ad empires seemingly overnight solely because they had the advantage of first-party data over companies like Meta, which were now in hot water over their reliance on third-party data. In order to use the TikTok app or Amazon’s services, you consent to give over large amounts of incredibly personal information that they have full right to use.

So far, the public hasn’t been as concerned about this as they were with cookies. However, the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022 would put limitations on these platforms that currently do not exist by redefining this data as not first-party data. The bill considers it third-party data as it originates from the platform, not the advertiser. As we’ve seen, that doesn’t mean the platforms cannot provide any of their data at all, but platforms like Amazon rely heavily on personally identifiable information for ad targeting.

Potentially Bad News for Small Businesses

Most of the rhetoric around targeted advertising and data tracking revolves around tech giants and large corporations, but the truth is, digital advertising is vital for many small businesses. This is especially true ever since the pandemic when many small local businesses took a huge hit. Obtaining a digital presence and being able to find their audiences online was for many, the difference between staying afloat and going out of business entirely.

It’s easy for a big company to hand over a huge list of their own first-party data for advertising purposes, but a small mom-and-pop shop can’t do the same for their small Facebook ad campaign. Digital advertising practices have plenty of downsides and major flaws worth addressing, doing so in this way might take away its best trait; allowing small and local businesses to harness the same tools large corporations regularly use to out-compete them.

The Banning Surveillance Targeting Act Is Dangerously Broad

Some parts of the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act go a little too far in an attempt to cover all the bases of potentially invasive ad targeting, resulting in broad points that would be difficult to navigate in practice.

For example, an advertiser’s first-party data is OK to use – email addresses, phone numbers, etc. – but cannot include data that could target someone as a member of a protected class. That wording implies that it’s perfectly fine for an advertiser to target your personal information so long as they have it already, but not discern whether your gender would make you more or less interested in an advertisement for female beauty products.

There’s another issue with the same point: what if your product or service is specifically for a protected class? It seems a bit silly that a custom walking aid-maker couldn’t target those in need of canes, or a mosque couldn’t target fellow Muslims to spread the word about its charity services. This ties back to small businesses as well – it doesn’t hurt Heinz that much to avoid targeting in this way, but it can hurt small businesses in specialized industries seeking to serve members of protected classes very much.

Lastly, there needs to be more specification surrounding information that can indirectly identify someone, because as it stands, it leaves a huge gaping hole of potential legal troubles. For example, if a name can easily imply a person’s gender, is that now prohibited if it’s included in their email address on a first-party data list? What if their search history includes information relevant to their race or religion? When you consider algorithms and their role in detecting patterns, how is a platform or advertiser reasonably supposed to avoid this data being used in ad optimization even if their intent was never to directly target that trait?

It’s possible that the answers to these questions aren’t bad news for advertisers – but that needs to be specified.

However, Contextual Advertising Already Exists

The controversy around third-party data and cookies for ads is not new, and advertising platforms have been developing cookie-less advertising methods for years. Granted, that doesn’t mean they made the full switch over to cookie-less methods or self-enforced bans on third-party data tracking, but it means that even if the bill passes in its current form, it wouldn’t kill digital advertising. It would just make that evolving switch over to alternative methods much faster and perhaps a bit more chaotic.

For example, we recently covered Snap’s Advanced Conversions system, which uses data obfuscation, contextual data, and cohort analysis to provide advertisers with better ad optimization and campaign reports without ever using identifiable information. They’re far from the only ones to have such a system in the works or already in place; though each platform’s method differs, they all strive to avoid most or all of the data being prohibited in the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act.

We Can’t Draw Conclusions on The Act Yet – Here’s Why

All that being said, it’s highly unlikely the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act is going to get very far – at least, it won’t without tons of significant changes – so speculating on its outcomes with any confidence is not productive. Why is this the case? Well…

Most Bills Die in the House of Representatives

Over 11,000 bills make it to congress, but only 7% ever become law.

It’s important to stop and realize that even though the internet has been going crazy over the BSA, it won’t necessarily go anywhere. In all likelihood, it will die in committee or get voted down – basically, it’s a lot of bark with little evidence it’ll ever bite.

No Act Goes Through Congress Without Extreme “Revisions”

Even if the BSA passes, it will not be passed as is.

When the Affordable Care Act finally passed, it had over 100 amendments. The Patriot Act started as a nine-page document, which eventually ballooned to over 300 pages by the time it was finalized.

The point here is, the 20 pages of information in the BSA are difficult to discuss in the first place when you consider how unrecognizable it will be by the time you should start becoming concerned.

Don’t Forget About Lobbying

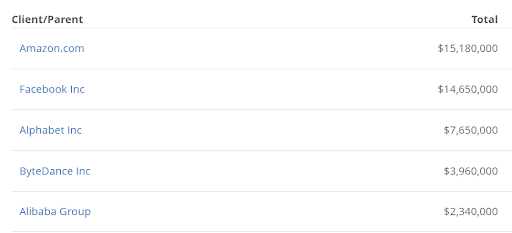

Here are the top five companies involved in congressional and federal lobbying for Internet-related matters:

Notice some familiar names? It’s not surprising, but lobbying on behalf of tech giants post-2016 increased by tens of millions of dollars:

“In recent years, the tech industry giants have shelled out large amounts of money especially in response to criticism from lawmakers over privacy issues, antitrust concerns and more.” Krystal Hur, OpenSecret.org

Is it widely speculative to assume a bill might be shot down entirely because of a few lobbyists? Maybe. It’s about as wild as the fact that dozens of congress members become lobbyists. Or the fact that businesses spend more money lobbying Congress than taxpayers do to fund Congress. Or as wild as the fact that the love affair between lobbyists and Congress members isn’t always figurative.

The fact of the matter is, lobbying of Congress might convince enough members to represent the idea that the BSA Act should die in Congress; as most bills do. It’s important to keep that in mind no matter where the majority public opinion seems to be, or the opinion of many advertisers — money talks, after all.

Why Was the Bill Introduced?

The US is Lagging Behind on Tech & Data Policy

The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act may be a reaction to the rapidly changing trends of targeted advertising and increased user privacy prioritization that is already underway. To put it another way, consider the bill as potential government-backed enforcement of changes that have already started rather than an entirely new and/or sudden change. These are, after all, industry practices that have been under scrutiny and debate for years, rather than new or ground-breaking developments.

The GDPR and other European regulatory and legal bodies have been policing large advertising platforms and other tech firms in a very similar way. Aside from this, many big businesses have taken steps away from typical data gathering methods, such as Apple and the tracking opt-out included in the iOS14 update. Others like Google have already started phasing out third-party data and cookies on their own, albeit less swiftly.

The Cambridge Analytica Scandal Made Political Involvement Inevitable

Tech companies enjoyed a long reign of self-regulation and little intervention from the government. Digital advertising methods were no exception, but that all changed after the Cambridge Analytica Scandal with Meta (formerly Facebook). As AdvertiseMint CEO Brian Meert notes, “No one really knew where the line was, but in 2016, everyone knew they crossed it.”

A vocal group of concerned citizens, including privacy-oriented companies like DuckDuckGo and Mozilla, had been raising alarm bells long before 2016. However, the scandal alerted everyone to the fact that this invasiveness concerned more than personal privacy – when in the wrong hands, it could influence democratic and political processes, and that self-governing policy clearly had not prevented this worst-case scenario.

Considering this, it was a matter of when not if the US government got involved, because Meta’s massive misstep in 2016 forced them to. Why it took them over five years to do so is anyone’s guess – hopefully, it was to become familiar enough with the digital world that they’re not so obviously out of touch this time around.

Common Viewpoints Surrounding The BSA of 2022

For those in favor:

It’s undeniable that some sort of legislation needs to be in place surrounding how data online is tracked and used by private companies. The fact that we made it this far without only makes sense when you watch just out-of-the-loop government officials are about the Internet, let alone decide on some sort of policy.

Either way, the bill is not too far away from similar regulations in place within European agencies. Entities like the GDPR aren’t perfect, but they’re also a step in the direction the majority of digitally native voters want privacy laws to go in.

This point gets skipped over a little too easily by marketers and other industry professionals when they discuss the impact of privacy laws. Too often, the discussion is framed as a potential detriment to a great method of reaching the right customers, as if customers aren’t aware of how much they benefit from targeted ads. This completely ignores the main point, that it’s the method in which targeted advertising is done that is the primary concern.

It also ignores the fact that most of those customers were never ok with that method in the first place. The reason this issue became such a big controversy wasn’t a sudden shift in public opinion; it was because few were aware to the extent their privacy was being invaded nor the implications this could have beyond selling products. By the time they found out, any hope of re-establishing that trust was long gone.

For those against:

All of the above is a completely reasonable point of view, but that doesn’t make the Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022 a reasonable solution. Regulation for data tracking and the use of data in advertising needs to at the least, draw a clear line for providers and advertisers to be aware of. As it stands, the bill is too broad to accomplish this.

Even if those specifications were to be made, it’s worth discussing whether those for the bill have a good perspective on who it is going after and hurting most. It’s easy to have no sympathy or concern for Meta, but the mood changes when you realize that it’s medical research, charities, and small local businesses that are impacted far more than any tech giant or corporation will be should the BSA pass as it stands.

Lastly, the public outrage and opinion don’t line up with the actions of most Internet users. The truth is, most of the very same people who voice concerns do not even bother to access the transparency tools they have access to, like public ad libraries, or Facebook’s complete account data logs and settings. Even fewer would be willing to pay for the platforms they’re seeking to limit.

It’s unreasonable to demand advertisers and platforms dismantle an entire economy like it’s a simple request. It’s even more unreasonable to simultaneously expect user benefits of the system you just abolished to remain.

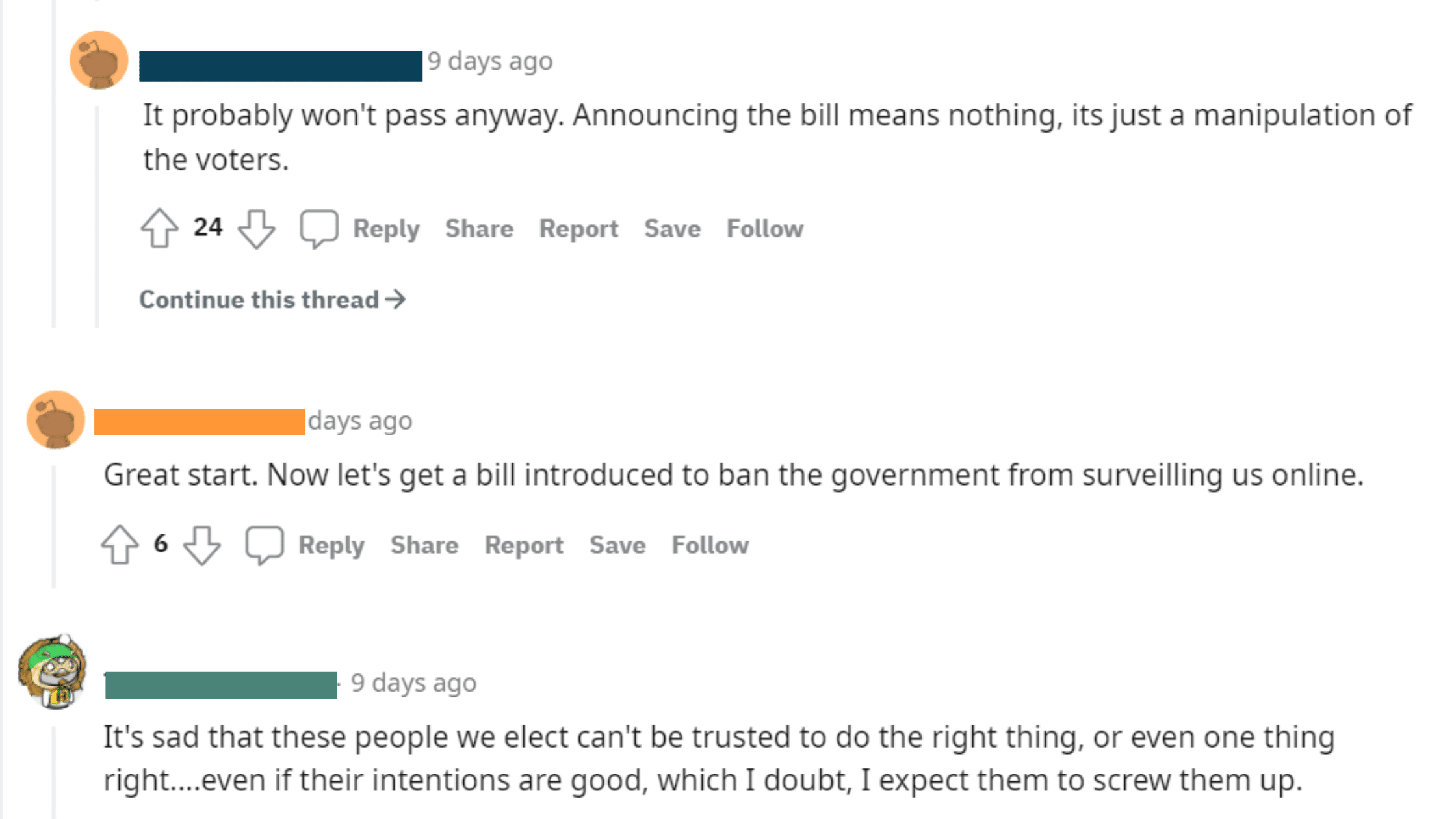

The Most Common and Least-Discussed Bipartisan Opinion:

The truth is, there is a consensus on the BSA across opinions and even party lines. It’s about the same as most bills, and it never gets discussed enough in the media. It sounds a bit like this, and speaks for itself:

Conclusion

It’s generally agreed across major parties that there are some issues with the current state of privacy laws when it comes to advertising. While they each have slightly different stances on how they would like to address these problems, we can all agree on the fact that The Banning Surveillance Advertising Act of 2022 is far too early on in its journey through Congress to start drawing conclusions or discussing outcomes. It’s worth keeping an eye on because it does have implications for advertisers, advertising platforms, and users alike.

Realistically though, this is now a matter of US Congressional processes. That’s a polite way of saying the Act will either go nowhere slowly or will have amendments that change the discussion entirely if it does go anywhere.